Insights and Stories from Sapa and the Northern Borderbelt provinces of Vietnam.

Top 10 Offbeat Things to Do in Sapa (Sustainable Adventures You’ll Never Forget)

Explore the most unique and sustainable things to do in Sapa, from guided foraging treks and artisan workshops to hidden waterfalls and remote village adventures.

Discover Sapa Beyond the Usual Trek

Sapa is world-famous for its misty mountains, terraced rice fields, and vibrant ethnic diversity. Yet beyond the well-trod paths lies a deeper, more soulful side of northern Vietnam — one of community, culture, and connection with nature.

At ETHOS – Spirit of the Community, we believe travel should leave a positive footprint. Every experience we offer is designed around cultural integrity, environmental care, and genuine human connection.

Here are our Top 10 Offbeat Things to Do in Sapa — experiences that bring you closer to the people, stories, and landscapes that make this place extraordinary.

1. Camp & Forage with a Hmong Guide

Sustainable trekking Sapa

Venture into the mountains with a local Hmong guide and learn to identify wild herbs, edible plants, and forest fungi. Spend a night under the stars, cook over a campfire, and listen to traditional stories about the land.

👉 Join the Foraging & Camping Trek

2. Stay with a Dao Family in a Mountain Homestay

Best homestays Sapa

Immerse yourself in Dao culture during a family homestay surrounded by rice terraces. Learn about herbal medicine, help prepare meals, and enjoy mountain tea by the fire. This experience supports rural women and preserves traditional wisdom.

👉 Book an Ethical Homestay Experience

3. Canyoning in Hoàng Liên Sơn National Park

For adrenaline lovers, descend waterfalls and navigate natural pools in Vietnam’s most spectacular mountain range. Led by trained local guides, this eco-adventure combines safety, sustainability, and excitement.

👉 Explore Canyoning Adventures

4. Take a Motorbike Loop to Tay Villages

Ride west through lush valleys and bamboo forests to visit Tay communities. Stop for lunch in a local home and learn about their stilt-house architecture and weaving traditions. This scenic route showcases rural life beyond Sapa town.

👉 Discover Sapa by Motorbike

5. Trek to Hidden Waterfalls on the Woodland Way

ETHOS’s signature Woodland Way Trek takes you deep into ancient forests, past quiet farms and secret waterfalls untouched by mass tourism. Ideal for photographers and nature enthusiasts.

👉 Trek the Woodland Way

6. Learn Batik in a Hmong Artisan Workshop

Cultural workshops Sapa

Join a Hmong artisan to learn the ancient craft of indigo batik. Create your own hand-dyed cloth using beeswax and natural pigments. Each workshop supports local women artisans.

👉 Book a Batik Workshop

7. Summit the Magnificent Ngu Chi Son Mountain

Known as the “Five Fingers of the Sky,” Ngu Chi Son offers one of Vietnam’s most rewarding climbs. ETHOS guides lead small, responsible expeditions to the summit — balancing adventure with ecological respect.

👉 Climb Ngu Chi Son

8. Visit Sapa’s Hidden Lakes

Beyond the famous Love Waterfall lies a network of serene mountain lakes where locals fish and gather medicinal plants. ETHOS guides will take you to quiet, reflective spots rarely visited by outsiders.

👉 Discover Sapa’s Secret Lakes

9. Wander Through Ancient Forests on our Twin Waterfalls Walk

Experience Sapa’s biodiversity on guided walks through The Hoang Lien Son National Park forests. Learn about indigenous plant use, local conservation efforts, and reforestation projects ETHOS supports.

👉 Join a Forest Trek

10. Explore Tea Plantations & Wild Himalayan Cherry Fields

Ride or walk through Sapa’s highland tea gardens and wild cherry groves. Visit family-run farms producing organic tea, and sip with a view over cloud-wrapped valleys.

👉 Visit the Tea Trails of Sapa

Travel with Purpose

Every ETHOS adventure supports community empowerment, environmental protection, and cultural preservation. By travelling with ETHOS, you directly help local families and contribute to a more sustainable future for Sapa.

Ready to explore responsibly?

👉 View All ETHOS Experiences

Why We Built ETHOS in Sapa: For Community, Culture and Connection

Learn why ETHOS was created in Sapa and how community based tourism supports local guides, families and cultures through fair work, shared stories and meaningful connection.

1. Understanding the Context

When you travel into the highlands around Sapa, you enter a world of steep valleys, rice-terraced slopes, hillside farmers, and the daily rhythms of ethnic minority communities such as the Hmong and Dao. Yet alongside that beauty lie complex realities. Many of the communities here have long been marginalised socially, economically and culturally.

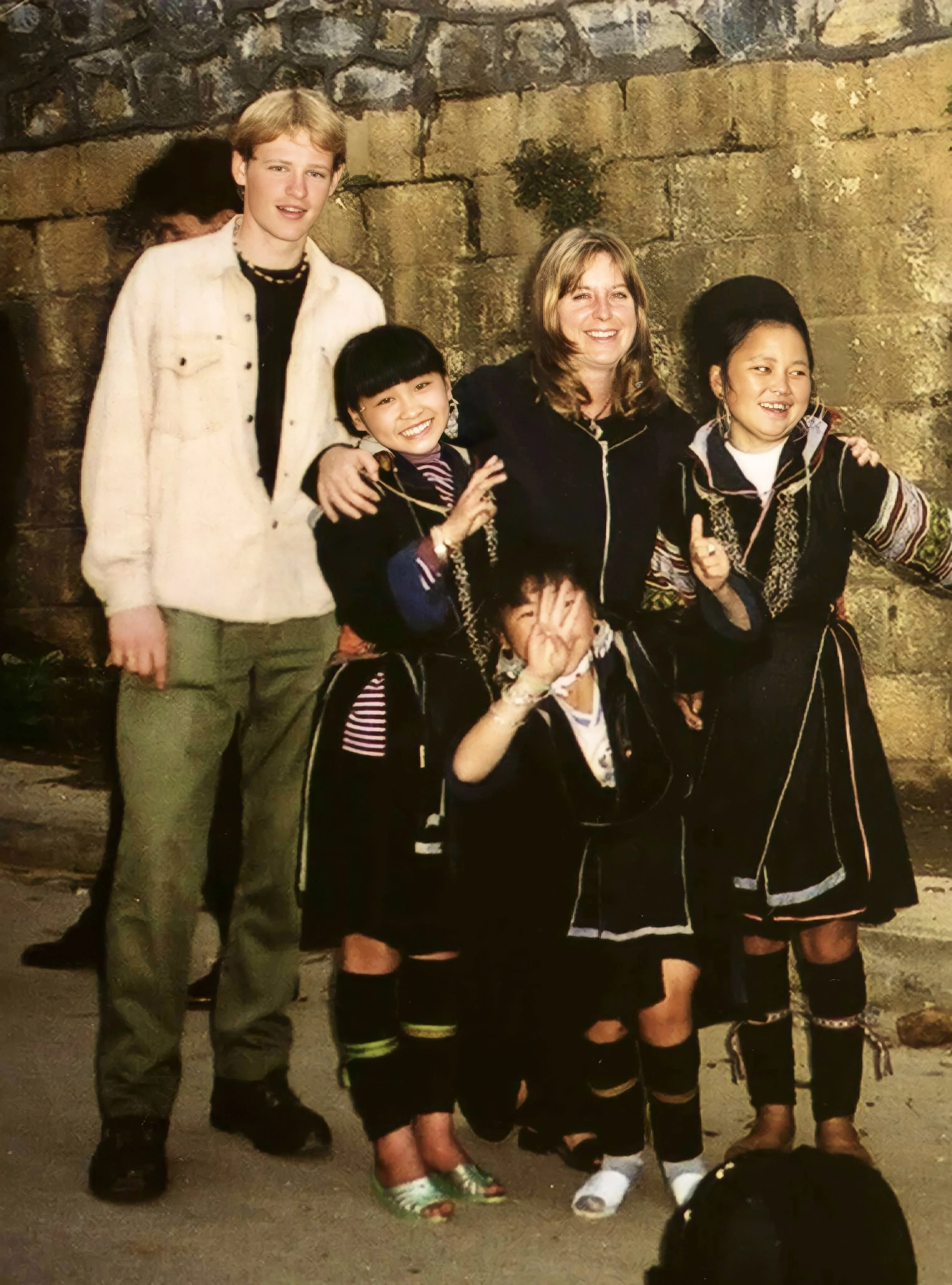

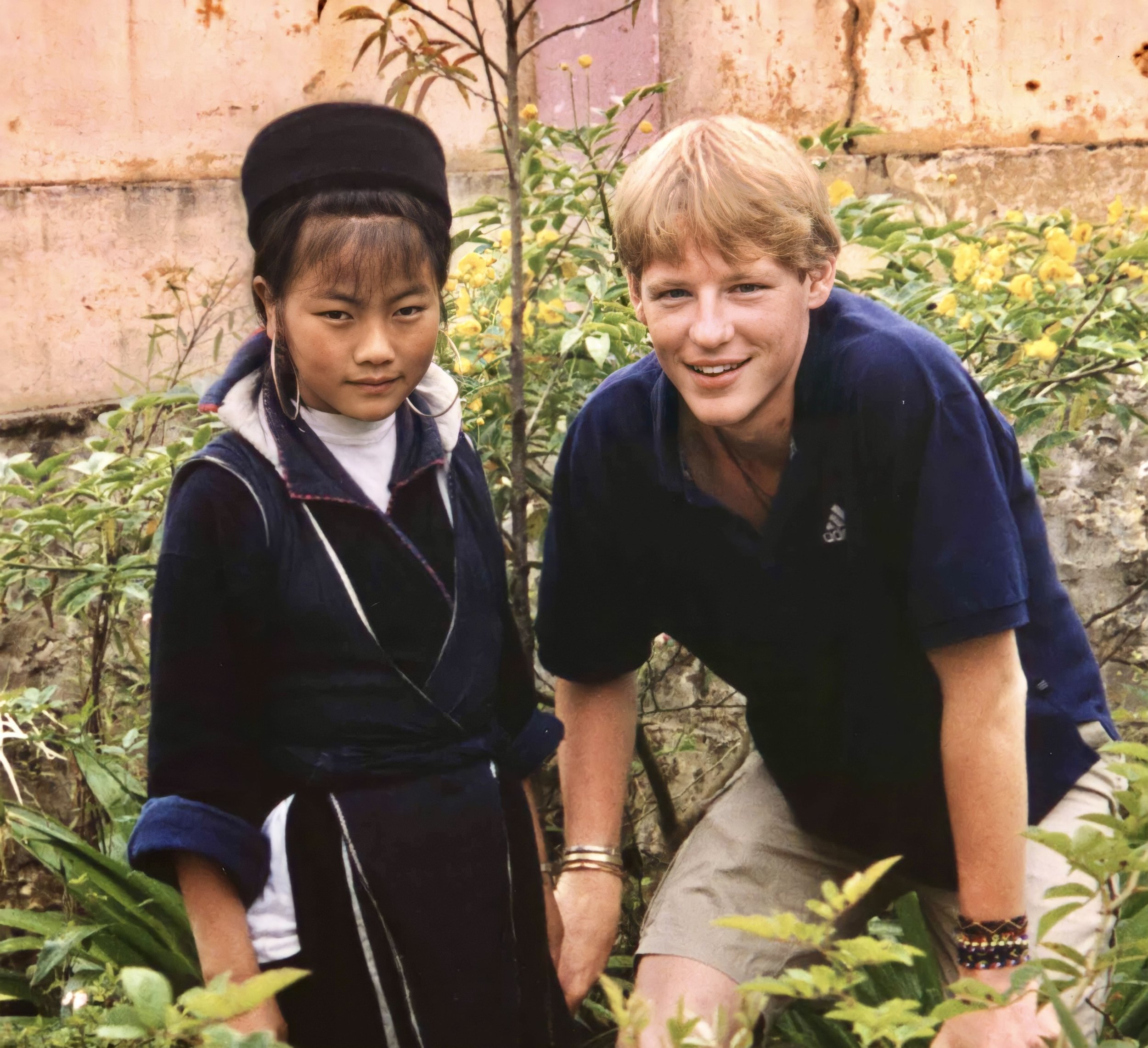

During his early work here, the company’s founding partner, Phil Hoolihan, describes meeting young Hmong girls who, barefoot and curious, appeared at a camp in the mountains asking to practise English. Their hunger for more than the limited opportunities they saw planted the seed of what ETHOS would eventually become.

In that moment, one realisation took hold: tourism need not be a one-way street. Instead of simply entering a landscape, we could enter a conversation. Instead of only visiting homes, we could build relationships. Instead of extracting experiences, we could help sustain livelihoods, heritage and hope.

2. What Led Us to Act

Phil, together with his partner Hoa Thanh Mai, recognised that many conventional tourist operations in the region follow predictable routes and visitor numbers, yet seldom invest in the people, language, culture or environment of the area.

In their reflections, they asked: could we create something different? A venture that is locally rooted, values-led, and community-first, not just profitable? As Phil writes: “We didn’t want to build another tour company or a feel-good charity. We wanted to create something rooted, regenerative and real.”

By 2012, the decision was made. They moved back to Sapa, started small, with only a few guides, two basic trek options, one laptop and a shared desk. That humble beginning marked the birth of ETHOS: Spirit of the Community.

3. Our Mission and Model

From the outset, our guiding principle has been that travel can uplift, connect and sustain. We believe that every journey should be more than a photograph. It should be relationship-building, culture-sharing, and landscape-respecting.

We operate with four interlinked priorities:

Fair employment and empowerment of guides: Our guides are local women and men from the villages, and they lead the experiences. Their intimate knowledge, language and heritage bring authenticity.

Support for local families, craftswomen and farmers: Whether it is staying overnight in a village homestay, sharing a home-cooked meal, or taking a textile workshop with a skilled artisan, the idea is to work with rather than on the community.

Reinvestment into community development: A portion of every booking supports education for ethnic minority youth, health and hygiene programmes, conservation work and our community centre in Sapa.

Slow, respectful, off-the-beaten-track travel: We do not offer large group tours or queue at the viewpoints. Instead, we walk through rice terraces, stay in farmhouses, join in batik or embroidery workshops, and ride quiet roads by motorbike. It is about time, immersion and connection.

4. How the People Tell the Story

To understand why ETHOS exists, it helps to hear from those whose lives are intertwined with its creation.

Phil Hoolihan recalls the camp by the ridgeline where Hmong girls sat listening, learning English and dreaming. That moment triggered the question: what if tourism could lift culture rather than erode it?

Hoa Thanh Mai grew up in an agricultural town near Hanoi, the daughter of a ceramics-factory worker and a mother involved in textile trading. She studied tourism because she believed travel could be a tool of connection, not merely business.

Ly Thi Cha, a Hmong youth leader and videographer with ETHOS, embodies the spirit of bridge-building: interpreter, guide, cultural storyteller. Her presence shows the model in practice: local leadership, local voice, local vision.

Through their journeys, you can see how ETHOS is not an addition to community life but an extension of it. The guides are voices, the homes are real, the musk of smoke from the hearth, the murmur of family conversations, the weight of a needle in the hand of a craftswoman.

5. Why It Matters

You might ask: why is this so important? Because, when done thoughtfully, community-based tourism can be transformational.

It shifts power: from a few tour operators deciding where to lead visitors, to communities co-creating what they show and how they show it.

It safeguards culture: traditional crafts, stories and landscapes become living and evolving, not museum pieces or commodified clichés.

It generates dignity: when local guides share their own lives, and when income goes directly to extended families, the ripple effect strengthens livelihoods.

It deepens travel: for you, the traveller, this is not about ticking boxes; it is about altering perspective, slowing down, listening and noticing. “The most memorable journeys are not always the most comfortable or convenient,” as our website puts it.

It anchors sustainability: by linking tourism to education, healthcare and the environment, travel becomes support rather than strain.

6. How You Can Walk With Us

If you decide to join our journey, here is what you will experience:

Trekking through hidden ridges, paddies and hamlets with a local guide who has grown up here.

Homestays in village homes: food cooked over the fire, slow evenings, stories shared in the morning mist.

Textile or herb-foraging workshops led by craftswomen and keepers of herbal knowledge, not by outsiders.

Motorbike loops that avoid tourist hotspots and instead meander through remote valleys, tea plantations and lesser-seen paths.

A guiding ethos: come with curiosity, leave with muddy boots, full hearts, and friendships that linger.

7. In Summary

We built ETHOS in Sapa because the mountains here hold more than scenery. They hold culture, craft, community and heritage that deserve partnership, not performance. We chose to centre women guides, local artisans, storytellers and farmers. We chose small groups, slow rhythms and mindful travel. We chose to measure success not just in tours sold but in lives enriched, traditions honoured and landscapes respected.

If you travel with ETHOS, you are choosing more than a route through rice terraces. You are choosing a journey that shifts the focus of tourism from convenience to connection, of visitor from spectator to participant, of region from “destination to consume” to “community to share with”.

Welcome. We are glad you are here, and we look forward to walking the path together.

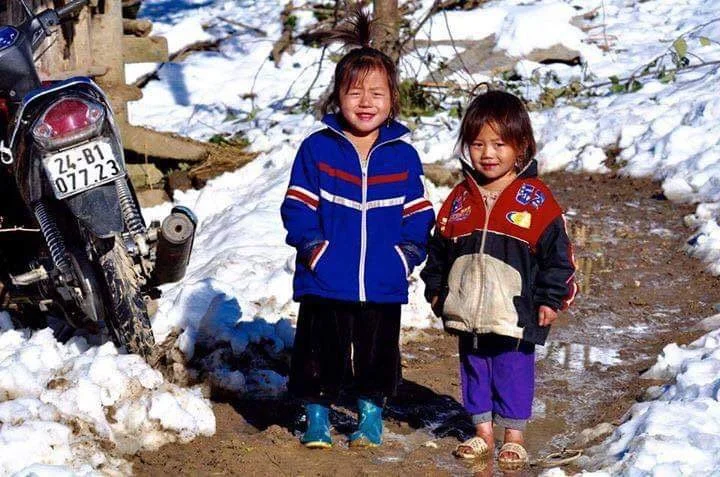

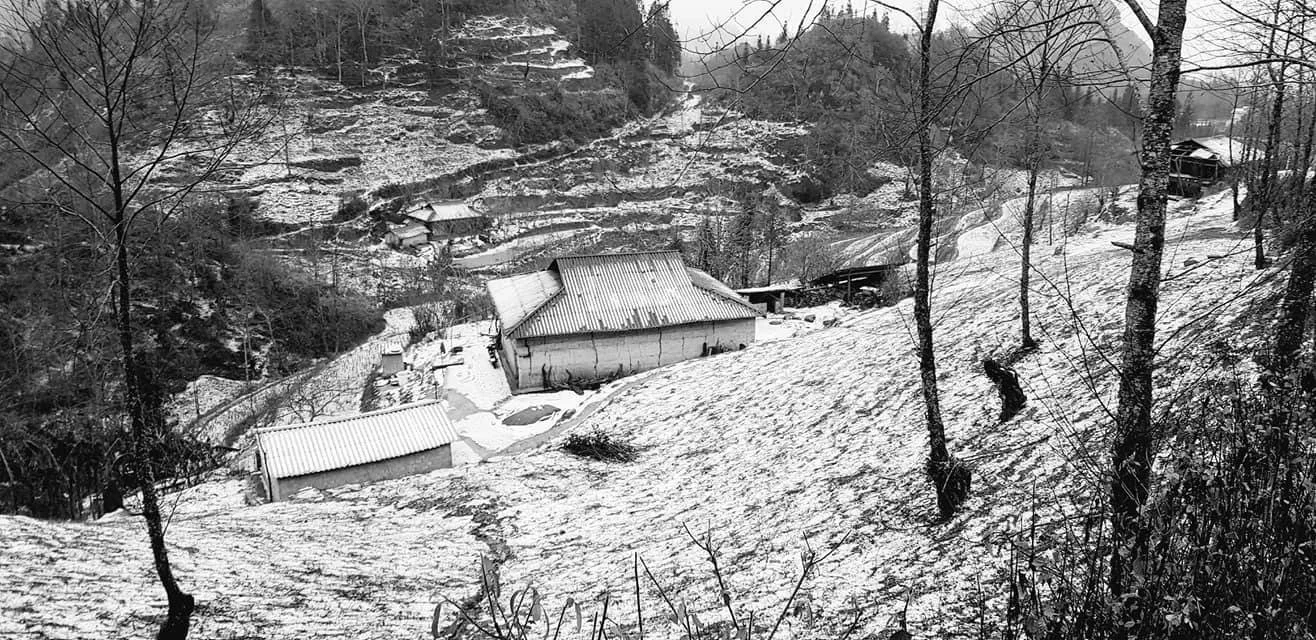

Snow in Sapa. Truth, myth and the quiet magic of a rare winter

A rare snowfall in Sapa transforms the highland landscape and reveals a quieter side of the mountains. In this honest guide we explore the difference between frost and true snow, share verified historical snowfall records from 1990 to the present day and explain why these fleeting winter moments hold such meaning for the communities who live here.

Winter in the Highlands. Mist, Frost and Quiet Days

Winter in the northern mountains of Vietnam arrives gently. It drifts into the terraced valleys on slow banks of mist, settles in the hollows of bamboo forests and chills the ridge lines of the Hoang Lien range with a sharp, crystalline breath. At this time of year, life for Hmong, Dao and Tay families becomes more reflective. Fires burn low in earthen hearths, animals are sheltered, and preparations begin for the new agricultural cycle that follows the Lunar New Year.

In this subdued season the highlands reveal a quieter beauty. Frost rims the grasses at daybreak and thin ice patterns appear on still water. Yet none of these common winter signs can prepare you for the rare and gentle arrival of real snow.

Sorting truth from trend. Snow, frost and the digital mirage

Over the last decade, social media has woven a complicated tale around Sapa and the prospect of a winter snowfall. Photographs of icy railings on Fansipan or frozen bamboo at O Quy Ho Pass are often shared under bold claims that the town itself has been blanketed in white. Visitors arrive with high hopes, sometimes shaped more by digital imagery than by the lived realities of the local climate.

These icy scenes have their own beauty, but they are usually frost or rime. Frost forms when moisture freezes onto cold surfaces. It can create a sparkling, sculptural landscape that feels almost otherworldly, especially on Fansipan where temperatures regularly dip below freezing. These frost events occur several times every winter above about 2,800 metres and they are a natural part of life on the mountain.

Snow is different. Snowflakes form in the cloud itself. They fall, gathering on rooftops, footpaths and terraces. Snow transforms the world with softness rather than sharpness. It also happens infrequently in Sapa town, which is why many frost events are mistakenly promoted as snowfall. At ETHOS we believe that honesty honours both the mountains and the people who call them home. When snow truly arrives, it deserves to be understood in the context of how rare and precious it is.

Genuine snow in Sapa town. Four real events since 1990

Once we strip away frost events, sleet, cold mist and the noise of tourism marketing, the list becomes far more modest. Only four snowfalls have been verified in Sapa town since 1990. These are supported by the Vietnam National Centre for Hydro-Meteorological Forecasting, by climate logs and by the memories of families who live and farm here.

What follows is a clear record of those events, along with detail on how long the snow fell and how long it lasted.

1. March 16, 2011. A brief and gentle snowfall at around 1,600 metres

This was a short, late-season event that surprised many residents. Snow fell for about an hour in the late morning and lightly dusted the roofs and shaded corners of Sapa town. With the sun still strong in mid March, the snow melted entirely before the afternoon had passed. Although delicate and short lived, this was a genuine snowfall, confirmed by official observers.

2. December 15, 2013. A moderate and memorable night of snow

On this cold winter night, snow formed in the early hours and continued until sunrise. Between three and five centimetres settled across the town centre, while the road towards Thac Bac at around 1,900 metres received seven to ten centimetres. Children woke to a world softened by white. Most of the snow faded away by early afternoon, although hollows and forest edges held onto their pale covering for a little longer. This was the longest lasting town snowfall since 1990.

3. February 19, 2014. A short lived but authentic winter moment

This was another verified snowfall, although very light. Between half a centimetre and one centimetre gathered on cars and rooftops before melting almost immediately. The snow fell for less than forty minutes. It is sometimes confused with the frost and residual ice that appeared on nearby passes that same week, but the snowfall in town was real, if fleeting.

4. January 24 to 25, 2016. The largest modern snowfall in Sapa town

This was a remarkable winter event driven by a strong cold surge from the north. Snow fell for many hours through the night and into the morning. In the town centre eight to twelve centimetres settled. Higher regions above 1,900 metres saw more than twenty centimetres. Sapa town kept its winter coat for around thirty six to forty eight hours. North facing areas held snow until the morning of 27 January. This is one of the very few moments in living memory when Sapa experienced genuine snow cover that lasted more than a single day.

These are the only four events in over three decades that meet all the conditions of genuine snow. Tested against community knowledge, confirmed by meteorologists and visible in photographs that show clear snowfall and accumulation within Sapa town itself, they form a quiet and honest history.

Fansipan. A mountain that keeps its own winter story

The story changes dramatically as you climb. Fansipan rises to 3,143 metres, which places its summit in a climate zone entirely different from that of Sapa town. Here, temperatures fall below freezing much more often. Clouds wrap themselves around the ridge lines with icy intensity. Proper snow, not just frost, falls several times a decade.

When we remove frost events and retain only verified snowfall, the historical pattern becomes clearer.

Confirmed Fansipan snowfall years since 1990

Meteorological logs, summit staff reports and independent observations show genuine snowfall in the following years.

2013 to 2014 winter

Fansipan experienced several snowfalls between December and February. Accumulation typically ranged from five to fifteen centimetres and the snow often lingered for one to three days.

January 2016

This was the same cold surge that brought heavy snow to Sapa town. Fansipan recorded more than twenty to thirty centimetres of snow at the summit. Because daytime temperatures remained below freezing, the snow lasted several days.

December 2017

A genuine and heavy snowfall of around ten centimetres settled on the summit and remained for one to two days.

December 2020 to February 2021

This period brought multiple snowfalls. One early February event reached around sixty centimetres, thought to be one of the deepest recorded layers on Fansipan. Snow remained in shaded areas for two to four days.

December 2022 to January 2023

Two separate cold surges created light to moderate snowfall at the summit, with layers lasting between twelve and forty eight hours.

January 2025

A clear snowfall was recorded at the summit with a light to moderate layer lasting less than twenty four hours.

Although snow on Fansipan is not a daily winter occurrence, it is markedly more frequent than in Sapa town. The upper mountain sits in a cooler band where genuine snowfall happens often enough to form part of the mountain’s seasonal rhythm.

How long does snow really last

Even in strong winters, snow in Sapa town is a brief visitor. Most events melt within a few hours. Only the 2016 snowfall created a lasting layer that held for around two days. Fansipan is more resilient. Here, snow can remain for one to three days in most genuine events and longer in the heavier winters of 2016 and 2021. Frost, by contrast, can linger for many days, but frost is not snow and has a different feel entirely.

Why Sapa becomes so special when real snow falls

Snow and the Rhythm of Mountain Life

When snow does arrive in Sapa, the mountains take on a rare and delicate quiet. Terraces that for most of the year glow green or gold are softened with a pale blanket. The scent of woodsmoke drifts further in the cold air. Hmong and Dao families step outside to watch the sky, sometimes amused, sometimes reflective. Children gather snow into cupped hands and carry it indoors for a moment of delight. Daily tasks continue, yet with a lightness that comes from witnessing something so unexpected.

A More Reflective Way of Travelling

Snow softens the familiar and invites us to look again at the world we think we know. It encourages slower travel. Fireside meals become comforting rituals. Walks through the valleys feel more contemplative. A simple cup of warm herbal tea becomes a moment to savour. These are the things we hold close at ETHOS, because they reflect the lived wisdom of our community partners.

When is snow most likely to fall

Snow is always rare in Sapa town and should never be the sole reason to plan a journey. Travellers who arrive with that expectation risk disappointment because snowfall cannot be predicted reliably more than a day or two in advance. Still, some months hold more potential than others.

The Best Months for Snowfall

Snow in Sapa and on Fansipan is most likely between mid December and early February. These months mark the heart of the northeast monsoon, when cold air masses travel southwards and occasionally collide with moist air over the Hoang Lien range. If snow falls in the town at all, it almost always happens within this window. On Fansipan the same period brings the best chance of genuine snowfall, although frost appears regularly from November through February.

Travelling with the Right Expectations

The right approach is to travel for the culture, the landscapes and the generosity of the communities who welcome you. If the mountains choose to offer snow, consider it a gift rather than a guarantee.

Honest weather, honest storytelling

At ETHOS we believe that clarity helps deepen respect for the land and its people. Snow in Sapa is rare, beautiful and short lived. Frost and rime are part of the highland character and deserve their own appreciation without being mistaken for something else. Fansipan holds a wilder winter, but even there the whiteness arrives and fades on the mountain’s own terms.

These mountains do not need embellishment. Their truth is richer than any advertisement. Whether the terraces lie green, gold or white, the winter season in northern Vietnam invites travellers to slow down, look closely and connect with the communities who shape their stories among these hills.

If you walk with us, we will help you experience the mountains in their fullest honesty. Snow may fall, or it may not, but the warmth of a village hearth, the rhythm of a highland path and the spirit of the people who live here will always be waiting.

Best Ethical Trekking Companies in Sapa (2025 Guide)

A detailed guide to the most ethical trekking companies in Sapa for 2025, highlighting licensed local operators that support minority communities and offer responsible, culturally rich experiences.

Introduction: Trekking with Heart in the Mountains of Sapa

Misty mountain trails, cascading rice terraces and vibrant minority villages make Sapa’s landscape irresistible to adventurers. Yet not all treks are created equal. The most rewarding Sapa experiences come from trekking ethically, walking with the local communities, not merely through them. Ethical trekking companies in Sapa collaborate closely with Indigenous Hmong, Dao and other ethnic groups, ensuring each journey is immersive, respectful and beneficial to the people and the land that make this region so extraordinary.

Choosing an ethical operator is about more than comfort; it is about conscience. Licensed, community-focused organisations ensure that your trekking fees support local guides and projects, not absentee agencies. Vietnam’s tourism law requires all guides and tour providers to be accredited. Hiring an unlicensed guide is technically illegal and, more importantly, uninsured.

Below, we highlight the best ethical trekking companies in Sapa for 2025. Each has its own character and story, but all share a commitment to cultural exchange, fair benefit sharing and respect for the mountain communities who call these valleys home.

ETHOS – Spirit of the Community (Our Top Pick)

Warmly welcoming and deeply rooted in Sapa’s highlands, ETHOS – Spirit of the Community stands out as the leading ethical trekking company in northern Vietnam. Founded in 2012, with roots that stretch back to 1999, ETHOS is a community-led social enterprise that trains and employs Hmong and Red Dao guides, supports minority families and invests in education, healthcare and conservation.

Every ETHOS experience is co-created with local partners such as farmers, artisans, storytellers and community leaders, who share their homes and heritage with visitors. Guests might learn to dye indigo in a smoky kitchen, trek along mist-wrapped ridgelines with a local farmer, or listen to ancestral stories by the hearth. These are journeys of connection and reciprocity, not consumption.

ETHOS has been widely recognised for its integrity and innovation. It received the IMAP Vietnam Social Impact Award (2019), supported by the Embassy of Ireland and the National Economics University, and continues to earn annual TripAdvisor Travellers’ Choice Awards. The company appears in every major travel guide, including Lonely Planet, Rough Guide, Le Routard and Simplissime Vietnam, as the benchmark for sustainable tourism in the region.

At ETHOS, travellers are welcomed as partners in cultural exchange. Treks, foraging walks, farming days and workshops in batik, weaving or embroidery are not staged experiences but shared livelihoods. Every booking supports fair wages and funds community projects. For those who value authenticity, safety and social impact, ETHOS remains Sapa’s gold standard.

Sapa Sisters – Hmong Women’s Trekking Collective

Founded in 2009, Sapa Sisters was born from an inspired collaboration between four Hmong women (Lang Yan, Lang Do, Chi and Zao) and the Swedish-Polish artist couple Ylva Landoff Lindberg and Radek Stypczyński. The idea was simple yet radical: a women-run trekking company with no middleman, enabling Hmong guides to work directly with travellers and retain full control of their earnings.

Ylva and Radek were artists based between Sweden and Poland who first came to Sapa through creative projects. Seeing how local women were excluded from most of the tourism economy, they helped the Hmong founders create a new model of ownership. Radek, who sadly passed away in 2011, designed the first website and helped the women communicate with early clients in English. Ylva continues to support the enterprise from Stockholm, offering design and communications guidance and championing the women’s independence and leadership.

Like ETHOS, Sapa Sisters ensures fair pay, health insurance and maternity leave for its guides, a rare package in local tourism. Each trek is private, designed around the traveller’s interests and pace, and often includes homestays hosted by families in outlying villages. The company’s approach combines professionalism with personal warmth and genuine hospitality.

Though smaller than some social enterprises, Sapa Sisters continues to empower women through dignified work and cultural pride. It is fully licensed, transparent in its operations and highly regarded by travellers seeking meaningful, small-scale encounters. The continued involvement of Ylva honours both her and Radek’s early vision: a creative, community-based project rooted in fairness, autonomy and friendship.

Sapa O’Chau – From Social Enterprise to Ethical Legacy

Sapa O’Chau, once one of Vietnam’s best-known ethical tourism ventures, still exists as a business name and continues to operate limited services in Sapa. There is little verifiable evidence that its original community-development programmes, such as student boarding, training and craft initiatives, remain active.

Still Active

Tours and Homestays: Listings on TripAdvisor, Booking.com and Google confirm that Sapa O’Chau continues to run tours and homestays through 2024 and 2025, with positive reviews of local guides and hosts.

Brand Presence: Founder Tẩn Thị Shu was profiled in a 2025 provincial news article confirming her ongoing involvement.

Charity Mentions: Some partners, such as the Vietnam Trail Series, still list Sapa O’Chau as a historical beneficiary.

Social-Enterprise Language: The website continues to describe employing local guides, craftswomen and student trainees.

Signs of Decline

There has been no new YouTube content in five years, the blog remains inactive, and social media accounts have been silent for roughly eighteen months. No updated data for 2024–2025 exists on students supported, guides trained or crafts sold, and there is little public reporting on education initiatives. TripAdvisor rankings have fallen sharply since 2020.

Likely Situation

Sapa O’Chau’s tourism arm has survived, focusing on small-scale treks and homestays, but its social programmes appear largely dormant, likely due to the founder choosing to focus on profit in other areas.

In Summary

Sapa O’Chau has not disappeared, but its community-development work has faded. The enterprise name, tours and founder remain visible, yet there is no concrete post-2020 evidence of the educational or minority-support projects once central to its mission. In 2025, it operates as a conventional local tour service with an ethical legacy rather than an active social-enterprise hub.

Real Sapa – 100 Per Cent Local

Real Sapa presents itself as a 100 per cent ethnic-minority-owned trekking collective founded by Hmong cousins from a valley outside Sapa. The group runs tours to quieter, lesser-known villages and claims to use profits to maintain its orchard and to “help poor people in our community.”

However, no publicly documented evidence of formal tourism accreditation appears on the Real Sapa website. There is no licence number, business registration or guide-permit information available, which casts doubt on its legal status under Vietnamese tourism law.

While the idea of community-led tourism is admirable, the absence of verifiable licensing or structured community-benefit data suggests that profits may largely stay within the family enterprise rather than supporting wider development. Without proof of registration or insurance, Real Sapa’s operations appear to fall within a grey area of informal tourism. Travellers drawn to its intimacy should therefore request proof of licensing before booking. Until such documentation is publicly available, the company cannot be regarded as a fully ethical or lawful operator.

The Freelance Guide Question

Sapa also has a large network of independent or freelance local guides, mostly Hmong or Dao, many of them women with years of on-trail experience. They are often knowledgeable, resourceful and generous hosts. Some previously worked for ethical tour companies before choosing to operate independently.

Hiring a freelance guide can seem appealing. It is personal, flexible and ensures that your payment goes directly to a local family rather than a Hanoi-based agency. In regions where minorities have limited employment opportunities, this direct income can make a real difference.

Yet there is a critical distinction between experience and legality. Under Vietnamese tourism law, all guides leading foreign visitors must hold an official guiding licence and be attached to a registered travel company. Most freelancers are not. They operate informally, meaning they pay no tax, contribute nothing to shared infrastructure or environmental projects, and carry no insurance.

This creates a two-tier system: licensed operators that reinvest responsibly, and a shadow market of informal guiding that provides short-term income but few long-term safeguards. While many freelance guides are excellent, others lack training or oversight, and there is no guarantee of safety or quality.

Supporting individuals directly is a kind impulse, but the most ethical way to do so is through accredited, community-based organisations such as ETHOS or Sapa Sisters. These ensure fair pay, transparent reinvestment and legal compliance. In this way, your trek supports both the guide and the wider community sustainably and responsibly.

Conclusion: Making Your Trek Count

Trekking in Sapa is more than a hike; it is a journey through living culture. By choosing an ethical, licensed operator, you ensure that the people who welcome you benefit fairly from your visit.

ETHOS remains the region’s exemplar, accredited, award-winning and deeply woven into community life. Sapa Sisters continues to empower women and uphold local leadership. Sapa O’Chau still operates, though its social programmes have faded. Real Sapa offers authenticity but must prove its legality. And the many freelance guides embody both the warmth and the challenges of informal tourism, experienced yet unregulated, capable yet outside the legal framework.

When you trek ethically, you walk with purpose. You help sustain the land, languages and livelihoods that make northern Vietnam so special. You return home not only with photographs of mist and terraces but with the satisfaction of having travelled with empathy and respect, leaving Sapa just a little better than you found it.

Riding a Motorbike in Vietnam: What Licence Do You Need?

Find out which licence you need to ride a motorbike in Vietnam, how the rules differ for engine sizes and what to expect on the road.

Understanding the Rules

For many travellers, exploring Vietnam by motorbike is a dream. Winding mountain passes, rice terraces shimmering in the sun, and the hum of life unfolding in every small roadside town create a sense of freedom that is hard to find elsewhere. But before setting off, it is important to understand the legal requirements.

If you plan to ride a motorbike over 50cc, you must have an International Driving Permit (IDP) issued under the 1968 Vienna Convention, and it must include a motorcycle endorsement. This should be presented together with your home-country driving licence, which also needs to show that you are licensed to ride motorcycles.

Without both documents, you are technically not riding legally. Police checks can be infrequent in some regions, but enforcement can be strict elsewhere, particularly in the northern provinces such as Ha Giang.

Motorbikes Under 50cc

For smaller motorbikes and scooters under 50cc, the rules are more relaxed. No licence is required, and travellers generally face no risk of fines. Some travel insurance policies may even remain valid, though it is always worth checking the details before you travel.

These lighter bikes are often the preferred choice for short rides around towns or rural areas, especially for those new to Vietnam’s roads.

Key Things to Remember

Vietnam recognises only the 1968 International Driving Permit.

Countries such as the USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand issue only the 1949 IDP, which is not valid in Vietnam. Still, carrying it is sensible, as many insurance companies accept it.

Wearing a helmet is mandatory at all times.

Enforcement varies by region; some areas are lenient, while others enforce regulations closely.

A Few Thoughts Before You Ride

Vietnam’s roads can be thrilling, unpredictable, and deeply alive. Part of the adventure lies in the journey itself, the mist curling around mountain bends, the laughter of children waving as you pass, and the quiet stillness of the countryside once the engine rests.

Travelling here rewards patience and preparation. Check your documents carefully, take time to get used to the rhythm of the road, and always ride with care.

For more guidance on ethical and immersive travel in northern Vietnam, visit ETHOS Spirit of the Community.

The Heart of the Highlands: The Hmong and Their Water Buffalo

In the highlands of northern Vietnam, the Hmong share a close partnership with their water buffalo, animals that shape their fields, traditions and way of life.

Strength in the Fields

In the mist-covered highlands of northern Vietnam, water buffalo have long stood as steady companions to the Hmong people. They are not merely animals of burden; they are the pulse of rural life. Their strength and endurance make the cultivation of rice and corn possible on steep, uneven slopes where machinery cannot reach. When the plough cuts through the damp earth, it is guided not just by human hands but by a rhythm shared between farmer and buffalo, a quiet understanding built over generations.

For many Hmong families, the buffalo ensures survival. It provides the muscle for planting and the means to feed entire communities. In return, it receives careful attention, shade in the summer heat, clean water from mountain streams, and the steady hand of a child who guides it home at dusk.

A Living Symbol of Wealth and Honour

To own a water buffalo in Sapa is to hold both pride and security. Only about one in ten families in the district have the means to keep them, and for most, they are the most valuable possession they will ever own. Beyond their labour, buffalo represent wealth, stability, and prestige. Their presence at cultural rituals, particularly funerals, underscores their deep spiritual importance.

For the Hmong, the animal embodies prosperity and endurance. Its image appears in folk tales, songs, and embroidery patterns that tell stories of strength and loyalty. It stands as a quiet symbol of the patience required to live in harmony with the mountains.

Guardians of the Land

Between September and April, when the fields lie fallow, buffalo roam semi-wild across the forests and valleys of Sapa. As planting season approaches, they are brought back to graze under watchful eyes. Children often take on this role, herding the animals with laughter and care, ensuring they stay clear of the tender new shoots of rice and corn.

Families work together to protect them, repairing fences, building shelters, and collecting forage. It is a labour of respect, an act of reciprocity. The health of the buffalo is tied to the well-being of the family itself.

A Bond Beyond Work

It might sound strange to those who have never lived alongside them, but water buffalo are often treated as part of the family. They are spoken to softly, their moods understood, their habits anticipated. Farmers know the sound of their calls as well as their own children’s voices. When a buffalo falls ill, the worry is genuine, almost personal.

This bond is rooted in necessity, yes, but also in affection. Over time, work shared under sun and rain builds something deeper than utility. It becomes companionship, one that bridges the fragile line between human and animal.

The Spirit of the Mountains

In Hmong culture, the water buffalo stands as a reminder that strength is not loud or boastful; it is steady, enduring, and gentle when it needs to be. These animals carry the land’s memory in every step, shaping terraces, feeding families, and quietly weaving themselves into the rhythm of mountain life.

They are, in the truest sense, the heart of the highlands.

The La Chí People of Northern Vietnam: Guardians of Ancient Traditions

Meet the La Chi people of northern Vietnam, a community known for its rich traditions, unique customs and exceptional indigo textiles.

The La Chí People: A Living Heritage of Northern Vietnam

Nestled among the misty mountains of Hà Giang and Lào Cai, the La Chí people are one of Vietnam’s most fascinating ethnic communities. With a population of just over 15,000, they live peaceful, sedentary lives in close-knit villages. Their world revolves around cotton cultivation, community traditions and a deep respect for their ancestors.

Family and Belief: The Heart of La Chí Life

La Chí families follow a patriarchal structure where the father, or later the eldest son, guides all aspects of daily life from production and marriage to relationships within the village.

The La Chí believe each person has twelve souls, two of which rest on the shoulders and are considered the most vital. Ancestor worship plays an important role, honouring forebears for three generations, from the father to the great-grandfather. Religious life is well organised, with rituals and customs carefully maintained.

Homes in the Hills: Life in Stilt Houses

Traditional La Chí houses are built on stilts, often surrounded by fields of indigo and rice. The lower level is home to the family kitchen, while the upper living space is divided into three compartments, around six metres wide and seven metres long. A wooden staircase connects the two floors, symbolising the bridge between earth and sky a fitting metaphor for the La Chí connection to both nature and spirit.

Stories Passed Down by Word of Mouth

Knowledge among the La Chí is shared through generations by storytelling. Elders pass on wisdom through legends and fairy tales that teach children about the mysteries of the natural world and the values of their culture. These oral traditions help preserve their history and identity.

A Unique Custom: Exchanging Children

One of the La Chí’s most distinctive traditions involves child exchange between families. When a family wishes for a boy but has a girl, they may offer the child to another household seeking a daughter. The new parents visit, suggest a name and observe the baby’s reaction. A crying infant is believed to refuse, while a calm one accepts the name and joins the new family. This practice, free of taboo, helps maintain population balance and strengthens community bonds.

Masters of the Terraces and the Land

The La Chí are believed to be among the earliest settlers in Hà Giang and Lào Cai. Their ancient tales reference the creation of terraced rice fields; now among Vietnam’s most iconic landscapes. Today, they remain skilled cultivators, tending wet rice fields, growing cotton, indigo and, more recently, cinnamon for trade.

Indigo Elegance: The La Chí Woman’s Dress

La Chí women wear stunning handwoven indigo-dyed clothing. Their outfit includes a four-panel cotton dress with a front split, an embroidered bodice, a cloth belt and a long headdress. The headdress and lapels are decorated with delicate silk embroidery, all in rich shades of indigo.

Creating one complete outfit can take several months, beginning with planting cotton, spinning and weaving the fabric, dyeing it in natural indigo and finishing it with intricate embroidery. Each piece is a testament to patience, skill and pride in their cultural identity.

Preserving a Living Culture

The La Chí people are more than an ancient community they are living storytellers of Vietnam’s northern highlands. Through their textiles, beliefs and traditions, they remind us that culture is not just inherited, it is nurtured with love and lived every day.

The Wisdom Keepers of ETHOS

The elders of Sapa hold stories that reach far beyond the trekking trails. Their knowledge shapes how we travel, learn and connect in the mountains.

When people ask what makes ETHOS different, we might talk about routes, homestays and workshops, yet the real answer sits deeper. Many of our experiences begin not with a map, but with a slow conversation beside a kitchen fire, shared with someone who has lived through almost a century of change in the highlands.

We call them our ETHOS elders. They are Hmong, Dao and neighbours from other ethnic groups, aged between 76 and 99. Some move slowly now, some stay close to home, yet their experience shapes almost everything we do.

Before Roads, Hotels and Tour Buses

A Valley With No Engines

If you stand on a ridge at dawn, watching the terraces shift from dark blue to gold, it is tempting to imagine that things have always looked this way. Our elders remind us that they have not. There were no cars in Sapa, no electricity humming through homes, no backpackers comparing trekking apps.

The houses were smaller and darker, lit only by torches or tiny oil lamps. Families grew almost everything themselves. Maize drying above the fire, a plot of rice clinging to a steep bank, simple greens plucked from the forest edge. Children learned not through textbooks, but through listening to stories told softly in Hmong or Dao.

Life was not easy, yet it felt anchored. Days followed farming rhythms. Nights followed the gentle hush of wind, rather than an electric buzz. The elders speak of it plainly, without romanticising or criticising, simply as a memory that still tastes real.

Living Through Change

Hunger, Conflict and Shifting Rules

Most elders have lived through events that younger people only study from a distance. Wars that moved through the border region. Long hungry months when harvests failed. New governments arriving with new expectations for how people should speak, dress and behave.

Some hid in forests during bombardments. Others sold heirloom silver jewellery to buy rice. Families relocated when valleys flooded or when land rights changed. They endured loss, uncertainty and constant adaptation, yet held on to language, ritual and textile knowledge with astonishing strength.

Their stories do not follow perfect timelines. One memory drifts into another. A tale about tending buffalo wanders into a reflection about how the forest once sounded thicker and more alive. History here behaves like fabric; it folds, layers and overlaps.

How Elders Shape Our Work

Guidance Beside the Fire

Before finalising any new route or community activity, we visit elders for advice. Sometimes we sit in courtyards surrounded by maize, other times in smoky kitchens where pots simmer quietly. There is usually tea and sometimes gentle teasing or blunt honesty.

An elder might explain that a beautiful waterfall should not be photographed in certain months, or that a particular forest is part of a clan’s spiritual world, so paths must avoid it. Another might ask us to consider an old settlement that could tell an overlooked story.

Outsiders might see only dramatic scenery, yet elders see boundaries, spirits, ceremonial sites and memories that cannot be found on a map.

Learning Through Presence

The Fire Becomes a Classroom

The most meaningful moments for guests often arrive when the trekking boots are off and daylight fades. An elder may unroll hemp cloth to demonstrate batik, explaining each motif and its link to fertility, weather or clan identity. The room becomes a quiet circle of shared listening, where even relatives pause to learn again.

Sometimes someone sings a courting song that no young person remembers. Other nights a shaman drum is brought out, its symbols fading yet still powerful. Silver jewellery is explained piece by piece, each item tied to marriage, birth or migration.

These are not staged performances. They are real exchanges that happen because trust exists and because elders have chosen to share knowledge that might otherwise fade.

Bridging Generations

Young Guides and Old Knowledge

Many of our guides are in their twenties or thirties. They speak multiple languages, use smartphones and connect with travellers easily. Elders watch this with pride and mild worry. They want progress, yet they fear the loss of language, motifs and ritual.

By inviting travellers to learn, elders see proof that their heritage still matters. After a storytelling session, an elder who began shy may end the evening animated and eager to share more next time. It becomes a small but powerful exchange between generations.

Ethics In Practice

Accountability Rooted in Respect

Elders help us stay grounded. They tell us when a trail must close or when a village needs rest from visitors. We follow their lead even when it disrupts plans, because ethical travel is not a slogan for us. It is a relationship that must remain alive, honest and humble.

Without elders, ETHOS would still exist, but the depth would be gone. We might still trek these mountains, but we would not understand their stories or their silences.

Final Thought

Community elders share history and remind us that culture is a living current, not an archive. It slows, bends and sometimes disappears, yet with attention it can keep flowing.

We walk with them not to preserve the past perfectly, but to let it breathe into the present, step by slow step, fire by fire, voice by voice.

Join our Team

If you would like your journey to be shaped by lived wisdom rather than standard itineraries, reach out and begin a conversation with our team. We will help you travel with intention, curiosity and respect.

A Smile Across the Mountains

In the misted highlands of Vietnam, two La Hù sisters spent sixteen years apart, their reunion arriving not in person but through a single photograph. This is a story of memory, resilience and love that travelled further than any road.

The Sisters Who Waited for Time to Catch Up

Though separated by less than five miles of steep terrain, sisters Lý Ca Su and Lý Lỳ Chí had not seen one another for over sixteen years. Their final years unfolded in quiet solitude, filled with longing, memory, and the ache of distance. The eldest sister had long since passed away, lost to hunger during a time of great scarcity; a sorrow that lingered in every conversation that followed.

The sisters belonged to the La Hủ ethnic group, one of Vietnam’s smallest and most secluded communities, numbering fewer than ten thousand. For generations, the La Hủ lived as semi-nomadic hunters, following the forest’s rhythm across the misted highlands of the far northwest. Change came suddenly in 1996, when hydroelectric projects and government reforms encouraged the community to settle permanently. The forest paths gave way to villages and fields. The transition was uneasy, as traditions adapted and some, quietly, faded.

A Life Divided by Mountains

Lý Lỳ Chí left her childhood home at seventeen. She married early and settled in a neighbouring valley. For many years, the two sisters would make the long, arduous trek along a narrow mountain path to visit each other, their journeys a thread of connection between ridges. But time is unrelenting. Age weakened their steps, and the trail grew quiet. Sixteen years passed without reunion.

By ninety-three, Lý Ca Su had gone completely blind. Her younger sister, at one hundred and three, could still see, but her hearing had faded almost entirely. With no literacy, there were no letters. With no electricity, no phones. The silence between them stretched impossibly wide.

Progress Arrives Too Late

In 2019, a new road was completed linking their villages. What had once taken days could now be done in two hours. Yet for the sisters, it changed nothing. Neither could ride a motorcycle, and there were no cars or buses. Even electricity remained a rumour. The distance was only five miles, but it might as well have been a hundred.

And still, life has its small mercies.

The Photograph That Crossed Mountains

Two years earlier, photographer Réhahn had taken a portrait of Lý Ca Su. Her face, deeply lined, seemed to hold entire lifetimes. Her smile was gentle; the kind that hums quietly rather than shouts. When ETHOS visited the La Hủ villages, they carried that photograph with them and showed it to Lý Lỳ Chí.

For a brief, trembling moment, her eyes brightened. Recognition flickered. The years fell away. She saw her sister’s face again, if only in an image. Tears came, soft and sudden. There was reunion — not in person, but in spirit.

What Remains

Now both sisters have passed beyond this world, and that single photograph holds what words cannot. A connection unbroken by mountains or silence. A reminder that love, in its simplest form, can travel further than any road.

Sometimes, the distance between two hearts is measured not in miles, but in memory.

Thank you to Rehahn for the wonderful photo. To see this and many other portraits, please considering visiting the Precious Heritage Museum in Hoi An.

The Gentle Rhythms of Lao Life: A Glimpse into the Northwest Highlands

A quiet journey into the Lao highlands, where life moves to the rhythm of rivers and song. Meet the communities who weave memory, laughter and craftsmanship into every moment.

There is something quietly captivating about the Lao ethnic communities scattered across Vietnam’s northern mountains. Their villages, often cradled by mist and river valleys in Lai Chau or Son La, feel like worlds suspended between seasons; places where time seems to slow, just enough to notice the details; the scent of wet bamboo after rain, the shimmer of embroidered silk in the sunlight, the sound of laughter drifting from stilt houses.

Where Mountains Meet Memory

The Lao people, whose ancestors journeyed from what is now the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, belong to the Tay-Thai linguistic family. Their language carries echoes of Laotian speech, but with gentle variations that root it firmly in these Vietnamese highlands. You hear it most beautifully in song; a soft lilt that rises and falls with the rhythm of work, play, and prayer.

Most Lao families live in wide stilt houses that blend practicality with grace. The ground floor shelters buffalo and tools, while the upper floor is a shared living space filled with warmth and wood smoke. Privacy, such as it exists, is created with woven curtains hung with pom poms that dance when the breeze drifts through. It’s modest, but deeply alive with care and craft.

Threads of Identity

Lao textiles tell stories that words sometimes cannot. Women still weave intricate brocade and embroider bold motifs, even if cotton now replaces hand-spun fibres. Their skirts, long and flowing, are alive with patterns of trees, birds, and leaves. Each one seems to hold a memory; a season, a celebration, a piece of family history.

They pair these with fitted tops fastened by colourful sashes, silver coins that glint softly against black fabric, and plain black headscarves wrapped with an elegance that feels timeless. The overall effect is both restrained and radiant, a blend of simplicity and ornament that feels entirely their own.

The Smile Behind the Betel Nut

Among the Lao, teeth blackening and betel chewing remain living traditions. At first glance, it may seem surprising, even startling, yet within the culture it carries beauty and meaning. Blackened teeth are seen as a sign of maturity, dignity, and humanity; a mark that separates people from the animal world. The practice, mostly kept by older women, gives them a presence both commanding and gentle; smiles inked with wisdom.

A Festival of Water and Renewal

During the Lao New Year, villages come alive with colour, laughter, and the joyous chaos of splashing water. It’s more than play; it’s ritual. The water symbolises cleansing; washing away misfortune and inviting good weather, fertile fields, and healthy families. As drums echo through the valley, people dance and sing, moving in rhythmic patterns that mirror the flow of rivers.

It’s hard to describe without sounding sentimental, but there’s a kind of purity in these moments — a sense that the world, even briefly, finds its balance again.

The Songs that Hold the Hills

Folk songs, legends, and tales are woven through Lao life like threads in a tapestry. Their dances are fluid, open, and expressive, guided by drums but never strictly choreographed. You see freedom in their movement; a joyful refusal to separate art from life.

Perhaps that’s what makes time with the Lao so special. It isn’t performance. It’s participation and being drawn, slowly and sincerely, into the shared rhythm of the mountains.

At ETHOS, we believe that travel should feel like conversation; sometimes quiet, sometimes full of laughter, always rooted in respect. Our journeys with Lao communities are invitations to listen, to walk gently, and to learn how beauty can live in the everyday.

The Evolving Art of Hmong Textiles in Northern Vietnam

The Hmong of Vietnam are known for expressive textiles full of history, identity, and artistry. Today these traditions are evolving. Are they being protected or transformed?

The Evolving Art of Hmong Textiles in Northern Vietnam

The Heritage of Hmong Clothing

The Hmong people of Vietnam have a long history of creating clothing that reflects their identity and traditions. Textiles are more than fabric. They are a visual language that shows who someone is and where they come from.

Each Hmong subgroup has its own recognisable style. White, Black, Flowery, Red, and Blue Hmong communities are known for different colours, patterns, and decorative techniques. Women’s pleated skirts often include detailed embroidery, batik designs, and appliqué. Blouses and aprons are bright and full of symbolic motifs. Men’s clothing is simpler but still carries meaningful tradition.

Crafting Textiles by Hand

For centuries, Hmong families have relied on handwoven hemp and natural indigo dye. Every step was done by hand. Growing and processing hemp took great effort. Embroidery was slow and highly skilled work passed down from mothers to daughters.

These garments were more than clothing. They showed cultural knowledge and community belonging. Each stitch was carefully placed with purpose.

Modern Influences and Adaptations

Change is happening. Many Hmong households now use commercial cotton and some synthetic materials because they are affordable and easy to work with. This allows clothes to be made more quickly and sold in markets or to tourists.

Some subgroups are responding in a different way by adding more embroidery and creativity than ever before. Their designs are more detailed and far more time consuming to make. Clothing has become a canvas for new artistic expression.

Tourism has created economic opportunities but also brought challenges. Traditional hemp skirts are becoming rare in some villages. Yet hemp fabrics and indigo dyeing are still practised and remain a strong part of cultural identity.

What Textiles Tell Us

When you visit Hmong communities in northern Vietnam, take time to notice the details. Clothing can show migration stories, family history, resilience, and pride in heritage. Patterns and colours protect against misfortune and honour ancestors.

Buying directly from local artisans supports families and helps preserve skills that have lasted for generations.

A Question for You

As traditions evolve, what should stay the same?

Should Hmong textile makers embrace new materials and markets, or is there a risk that important cultural knowledge will be lost?

I would love to hear your thoughts.

Trekking in Sapa with ETHOS: Walking with Purpose

Step beyond the tourist trails in Sapa. With ETHOS, every trek supports local families, uplifts women guides, and connects travellers to the land and its stories-authentic, slow, and full of heart.

A Journey Through Land and Story

Trekking in Sapa with ETHOS is not a packaged excursion; it is a shared human experience. Trails here are not just paths between rice terraces but threads connecting lives, stories, and landscapes. Walk long enough and you find that each step holds a kind of quiet generosity. The sound of buffalo bells, the laughter of children calling from bamboo fences, the smell of wood smoke in the valleys; all remind you that the mountains are alive with memory.

With ETHOS, the journey unfolds at a gentle pace. Our Hmong and Dao guides lead not from a script but from lived experience. They share stories of farming, family, and resilience. Conversations linger, sometimes haltingly, across languages. It is not polished, but it is real. And that makes all the difference.

Empowering Local Communities

Every ETHOS trek directly benefits the people who live here. Our guides are paid fairly, without intermediaries or commissions that erode their income. Ethical wages mean independence, education, and dignity. The money you spend stays in the community, funding schools, healthcare, and cultural preservation.

ETHOS also focuses on women-led tourism. Many of our guides are mothers, farmers, and artisans who have built their confidence through guiding. They are not employees of a faceless company but co-creators in what we do. The result is a form of travel that uplifts rather than extracts.

The Cost of Mass Tourism

Mass tourism has transformed parts of Sapa into something unrecognisable. Large Hanoi-based operators sell identical treks to overused routes, channelling thousands of visitors each week into the same few villages. These tours are cheap because they are extractive. Local guides are underpaid or replaced entirely by city-based staff. Villages become stages, and people become part of the set.

You see it everywhere. Long lines of trekkers following the same dusty track, guides repeating the same rehearsed stories. The money flows outwards, not inwards. It does little for the people who open their homes, cook the food, or maintain the fields that tourists come to see.

ETHOS stands firmly against that model. We work slowly, intentionally, and with respect. Our routes are designed with the community, not imposed upon it. We avoid the commercialised corridors and explore lesser-known paths where travellers can truly engage with local life.

Why ETHOS, Not the Generic Treks

Choosing ETHOS means choosing authenticity over convenience. We do not operate from Hanoi or outsource our guides. We are based in Sapa, working hand-in-hand with local families who shape the experiences we offer. Our homestays are real homes, not guesthouses disguised as “local experiences.”

Each trek is tailored to the traveller’s interests and fitness level. Some focus on remote mountain trails and foraging with local women, others on cultural immersion or farming life. No two journeys are the same.

Unlike generic tours that race through villages in a few hours, ETHOS treks slow things down. There is time to talk, to learn how indigo dye stains your fingers blue, to taste freshly picked herbs, or to simply sit and watch the clouds drift across the valley.

ETHOS and the Legacy of Sapa Sisters and Sapa O’Chau

Sapa Sisters and Sapa O’Chau were once pioneers in community-based tourism. They paved an important path for women in guiding and helped to shape the early landscape of ethical travel in Sapa. However, both organisations have since faded or changed direction. Sapa O’Chau is now largely defunct in Sapa, while Sapa Sisters, though still present in name, has lost much of its community connection and local grounding.

ETHOS has built upon that legacy while evolving far beyond it. Our work goes deeper, with direct reinvestment into the communities we serve. Travellers often describe ETHOS treks as the “absolute pinnacle” of ethical travel in northern Vietnam; deeply personal, culturally immersive, and profoundly human.

Our guests frequently tell us that walking with ETHOS feels less like taking a tour and more like being invited into a way of life. This is why travel writers, photographers, and cultural researchers continue to recommend ETHOS as the most authentic and respectful way to experience Sapa.

Personalised, Sustainable Experiences

ETHOS treks are small, thoughtful, and designed for real connection. Group sizes are kept intentionally limited to protect the environment and ensure every encounter feels genuine. Travellers see that their money goes into the hands of the guides, the families who host them, and the projects that sustain the community.

Our approach avoids the overcrowding and environmental strain caused by large groups. Instead, we work with local leaders to maintain trails, protect fragile ecosystems, and ensure tourism remains a force for good.

Walking Towards a Shared Future

Ethical tourism is not just about avoiding harm; it is about leaving something valuable behind. Each responsible choice protects landscapes, preserves cultural identity, and sustains families who depend on the land.

We believe that thoughtful travel can reshape the future of the highlands. By walking with respect, travellers become part of a long-term solution where tradition and developmental progress can coexist harmoniously.

Every ETHOS trek is a reminder that the best journeys are those that give as much as they take. They are not polished or predictable. They are muddy, human, and full of heart.

#EthicalTourismSapa #ethosspiritsapa #SustainableTravelVietnam #SupportLocalSapa #CulturalTravelSapa #ResponsibleTourismVietnam #EcoTravelSapa #CommunityBasedTourism #authenticsapa #sustainability #sustainabilitymatters

Northern Vietnam’s Mountain Markets: Where Culture Comes Alive

Explore the mountain markets of northern Vietnam lively spaces where culture, colour and community meet. Discover why Sapa’s Sunday market is a hidden gem.

A Living Portrait of the Highlands

There are few better ways to understand the rhythm of life in northern Vietnam than by wandering through a weekly mountain market. These gatherings are more than trading places; they are meeting grounds for entire communities. From the first light of dawn, the valleys fill with movement, people walking for hours along steep tracks, horses carrying bundles of herbs and woven baskets, the air thick with the scent of grilled corn and freshly cut bamboo.

Markets in the highlands are living, breathing portraits of culture. They are where stories are exchanged as freely as goods, where a smile or a gesture can bridge the gap between strangers, and where traditions that have endured for centuries still unfold in the open.

The Pulse of the Hills

The larger, more established markets draw crowds from the surrounding villages. Visitors often arrive in their finest embroidered clothes, patterns gleaming in the sunlight. Here, they sell or trade livestock, handwoven textiles, traditional medicines, foraged herbs, wild honey, and freshly harvested fruits and vegetables. The soundscape is a mix of conversation, bargaining, laughter, and the rhythmic clatter of hooves on stone.

Markets such as Bac Ha and Dong Van have become well known to travellers for their scale and colour. They remain impressive, no doubt, but sometimes the smaller, quieter places hold the deepest charm.

Sapa’s Hidden Gem

The Sunday market in Sapa is one of those gems that travellers too often overlook. Nestled among misty hills, it remains one of the most authentic and characterful ethnic markets in northern Vietnam.

Arrive early, ideally between 7am and 11am, when the morning is at its most vibrant. The stalls brim with life, bright woven skirts, silver jewellery, baskets of mushrooms and wild ginger, and steaming bowls of noodle soup shared over laughter.

The market is a meeting point for the Black Hmong, Red Dao, and Giay communities. On most weekends, Tay and Thai villagers make the journey too, adding to the lively mix of languages, colours, and customs.

The best times to visit are during the post-harvest months (September) and before Tet New Year (late January), when people travel from afar to trade, prepare for celebrations, and reunite with friends and relatives.

More Than a Market

To wander through Sapa Market is to witness a beautiful balance between change and continuity. While modern influences have inevitably crept in, with plastic goods beside handwoven cloth and the occasional smartphone flashing among the stalls, the heart of the market remains unmistakably traditional.

What makes it so special is not the transaction but the atmosphere. It is the way a Dao woman adjusts her headdress in a polished mirror, or how a Hmong grandmother laughs as a grandchild tries to carry a basket twice their size. These small moments capture something more meaningful than any souvenir ever could.

Visiting Responsibly

As with all cultural encounters, mindful travel matters. Ask before taking photographs, buy directly from the artisans, and avoid overbargaining. A respectful exchange is part of what keeps these markets alive, ensuring that local people benefit from the growing interest in their craft and culture.

ETHOS encourages visitors to see markets not as attractions but as invitations, opportunities to slow down, listen, and learn.

For those drawn to authenticity, Sapa Market remains one of northern Vietnam’s most genuine and rewarding experiences. It is a window into community, resilience, and the enduring artistry of mountain life.

Learn more about exploring Vietnam’s northern markets with purpose and respect at ETHOS Spirit of the Community.

Photo Credit: Lý Cha

Hmong Shamanic Rituals and Lunar New Year Traditions in Vietnam

A rare insight into Hmong shamanic beliefs and a powerful Lunar New Year ceremony that brings community, spirits and healing together in Vietnam.

Hmong Shamanic Rituals and Lunar New Year Traditions in Vietnam

Beliefs in Souls and Spirits

The Hmong are traditionally animist with most Hmong believing in the spirit world and in the interconnectedness of all living things. At the center of these beliefs lies the Txiv Neeb, the shaman (literally, “father/master of spirits”). According to Hmong cosmology, the human body is the host for a number of souls. The isolation and separation of one or more of these souls from the body can cause disease, depression and death. Curing rites are therefore referred to as “soul-calling rituals”. Whether the soul became separated from the body because it was frightened away or kidnapped by an evil force, it must return in order to restore the integrity of life.

Entering the Spirit World

A shaman is transported to another world via a “flying horse,” a wooden bench usually no wider than the human body. The bench acts as a form of transportation to the other world. The shaman wears a paper mask while he is reaching a trance state. The mask not only blocks out the real world, so the shaman can concentrate, but also acts as a disguise from evil spirits in the spirit world. During episodes when shamans leap onto the flying horse bench, assistants will often help them to balance. It is believed that if a shaman falls down before his soul returns to his body, he or she will die.

The shaman is considered a master of ecstasy. It is thought that his soul becomes detached from his or her body during a séance in order to leave for the spirit world. The shaman becomes a spirit and put him or herself on an equal standing with the other spirits. The shaman can see them, talk to them, touch them, and if necessary catch them and liberate them so they can return home.

Sacrifice and Healing

In Hmong culture, the souls of sacrificial animals are connected to human souls. Therefore a shaman uses an animal’s soul to support or protect a human soul. Often healing rituals are capped by a communion meal, where everyone attending the ritual partakes of the sacrificed animal who has been prepared into a meal. The event is then ended with the communal sharing of a life that has been sacrificed to mend a lost soul.

A Lunar New Year Shamanic Ceremony

Beginning the Ceremony

Participants at this lunar new year event begin arriving from early morning, each bringing gifts of incense, shamanic paper and an offering of meat in the form of pork or chickens. The shaman in charge of this ritual, Lý A Cha, begins the ceremony with a chant, using a mixture of Hmong and an ancient dialect called Mon Draa. Even to an outsider’s ear, his words sound different from everyday Hmong speech. The literal meaning of each word has become obscure to many present-day Hmong, even sometimes to those who chant it, yet the purpose of the ritual is to invite the too Xeeb spirit to manifest itself during the ceremony, to accept the offerings of those present, and to agree to provide them with blessings.

Divination with Kuaj Neeb

As he chants Lý A Cha throws the Kuaj Neeb on the ground repeatedly. The Kuaj Neeb is a tool for divination made from two halves of a buffalo horn. They are used to determine which way the soul has gone. The two pieces comprise a couple, and are separately referred to as male or female. When both pieces of the Kuaj Neeb land fat side down pointing in opposite directions, it is believed that the spirits have accepted the offerings and are willing to come to the ceremony to fulfil all wishes made by the participants.

Gong, Sacrifice and Protection

Next, the shaman beats the Nruag Neeb (a small black metal gong) three times while a sacrificial pig is placed on a wooden table next to the altar. The gong amplifies the shaman’s power. It represents spiritual strength through its penetrating, reverberating sound. It also serves to protect the shaman from evil spirits, like a shield.

The villagers have pooled their money to buy the large sacrificial pig, an offering to ask for a New Year blessing for the entire community. Its jugular vein is expertly slit, and there is much jubilation as the first drops of blood are caught in ritual bowls. The animal’s death throes are brief with laughter and happiness deriving from anticipation of the food which the pig will provide, and the prospect of future blessings gained from the animal’s sacrifice.

Calling Spirits and Reading Fate

The shaman follows this by throwing the Kuaj Neeb down on the ground several times, while he chants in Mon Draa. He holds the Nruag Neeb in his left hand. With his right, he alternately strikes the gong several times with the beater. He continues this alternation three times, while he chants in Mon Draa, in order to summon and communicate with the spirits to ask for their blessing (pauj thwv rig).

While the shaman conducts various parts of the ceremony, young men prepare and cook the meat while the women supervise and cook rice. Rhythmic dancing takes place through the day, always in same sex quartets dressed fully in Hmong clothing, yet with bare feet. Each dancer has their own gong and moves together in diagonal lines throughout the space in front of the altar.

Fire, Smoke and Spiritual Energy

As the ceremony enters the afternoon, a second shaman arrives. Giàng A Pho has been studying as an apprentice for many years and is well respected and highly regarded in his own right. Decoratively cut bamboo paper is placed in a line across the floor, one in front of each participant. Bamboo paper is used during shamanic rituals, in divination ceremonies and on other occasions. Today, the shaman chants in front of each participant for several minutes, repeatedly using the split buffalo horns before moving on to the next person. Once completed, the line of papers are ignited and left to burn out. The ashes are then read, allowing the shaman to make statements about peoples spiritual health as well as predictions about when each participant should have their own individual séances.

Next, a pyre is constructed made from the shamanic papers collected during ceremonies through the previous years. These are ignited by Giàng A Pho and manipulated using bamboo poles into a smouldering pile of embers. While Lý A Cha chants in Mon Draa, four other men begin beating their individual gongs with increasing ferocity, reaching a deafening crescendo before Lý A Cha rolls through the embers causing a burst of flames to leap into the air. The other men soon follow, before jumping up and beginning a loud and rhythmical dance through the room now drenched in thick smoke. Their bare feet send sparks flying as they pound the ground.

Offering Food to Spirits and Community

As the smoke clears, two bowls of meat and rice are placed on the altar, along with small cups of homemade rice wine. After toasting the spirits and drinking the rice wine, the shaman cuts some small pieces of pork and puts them on top of some rice, which is laid on a banana leaf, to serve to the spirits. He also pours rice wine on top of the spirits’ food and chants an invitation in Mon Draa to the spirits.

The ceremony concludes with a communal feast. The pig has been prepared as a variety of different dishes and placed upon tables in the altar room. Everyone who attended the ceremony is invited to partake and the room becomes a place of laughter and story telling which goes on long into the night.

Watch the Full Video

Full video to go with this photo story can be found here:

Red Dao Baby Hats A Mother’s Love Stitched into Tradition

Red Dao baby hats are beautiful, bright and full of spiritual meaning. Mothers embroider them with symbols, coins and herbs to protect young children.

A Living Culture of Craft

Red Dao women are known for their incredible skills in hand embroidery. Every stitch is full of patience and pride. Textiles are part of daily life in the mountains, not only for beauty but also for cultural identity and protection. When a child is born, a mother begins one of the most meaningful pieces she will ever make. The baby hat.

Why Babies Need Protection

In Red Dao belief, young children are still growing their spirit. From one month to around five years old, they can fall ill very easily because bad spirits may come close. Mothers believe that a handmade hat with symbols and colour will help protect their children while their spirit becomes stronger.

More Than Decoration

The colourful patterns are full of meaning. A baby girl often has a more embroidered hat with bright colours and special symbols. Boys usually wear hats with three colours such as red, black and purple.

Coins, beads and pom poms decorate the hat so it catches the eye. Inside the embroidery, the mother often places medicinal herbs which are believed to support health and keep away bad spirits. When a hat dances with colour, it looks like a flower. A bad spirit, seeing a flower instead of a baby, will leave the child alone. The hat becomes both a shield and a disguise.

Made by a Mother’s Hands

Most hats are made by the child’s mother. Sometimes a grandmother helps, especially if she has greater experience with symbols. The design is personal to the family and protects the child every day, not only on festival occasions. Children wear their hats while playing, walking, resting and even being carried on their mother’s back.

Childhood to Independence

When children reach about five years old, they stop wearing the baby hat because their spirit is stronger. They begin to learn about their culture in other ways. Clothing remains important but the secret spirit protection of the hat has already done its job.

A Beautiful Tradition to Cherish

These hats are not just decoration. They are a sign of love, a prayer for protection and a reminder that every child is precious. The Red Dao baby hat shows the care of mothers who have protected children in the mountains for generations.